Architectural Theory

from “Contemporary Collective Formations”

Professor Lawrence Blough, Pratt Institute

May 2019

Mechanisms of Liberation Through Alternative Domesticities

In many degrees, and through many means, architecture and urbanism have seen a multiplicity of shifts throughout time towards alternative and sometimes unconventional domesticities. While some feature a leap towards technology and modernism, others retreat into pastoral utopias. The simultaneous unconventionality and attractiveness of collective and alternative means of living lies in the loose definition of the internal and external political, social, and economic thresholds. The openness of these accommodations creates relationships between people and nature in varying degrees, and expands the idea of the home out of that of a shelter and into a broader envelope of criteria. “This dissolution of the boundary in a multilayered space can provide much more effective protection than that offered by pathetically thick walls and doors.” The ability of these dwellings to address ownership and to form or negate a sense of community varies, but the flexibility and porosity can be likened to the Japanese engawa. Providing a spatial richness, the engawa is flexible in defining interior and exterior space, and cannot be limited to the linear definition of a door. Similarly, many alternative domesticities cannot be limited to their capacity to accommodate the nuclear family.

In his book, Living Complex, Niklas Maak describes the phenomenon of the cave as an existing spatial condition that encompasses and embraces the act of settling. Maak says, “the act of settling in is fundamentally different from the act of building” (114). The settler, or settlers, can be defined by the cave being inhabited as well as the means and motivations by which its inhabited. “To appropriate something means basically only to manifest the supremacy of my will in relation to the thing and to demonstrate that the latter does not have being for itself and is not an end in itself” (Hegel, Lee, 56). For the purpose of this argument, two housing phenomenons and their emergent contrasting qualities and effects on the dwellers throughout the process of settling will be analyzed as typologies of the inhabitable cave. Additionally, each phenomenon will be analyzed as parts of wholes and as scalar beings in their emergent communities (or lack thereof).

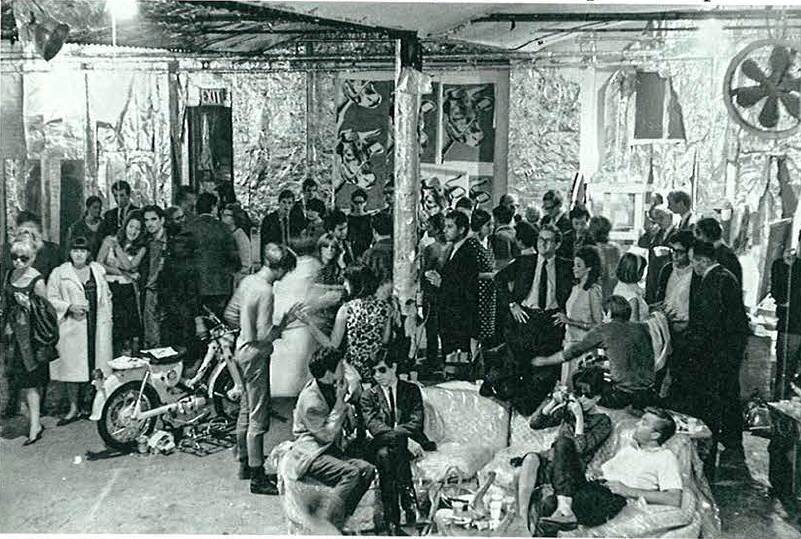

This first emerged as the result of sociological and political frustrations that lead to the rise of an alternative urban counterculture in the United States during the 1960’s through 80’s. The acceptance of capitalism and unconventional means of living and co-living resulted in the spatial appropriation of industrial workplaces that ushered in a completely new way of experiencing the social, economic, and political atmosphere in the urban setting. An urban commune, within the heart of a city representative of capitalism, Andy Warhol’s Factory attracted people from all around the country and the world, as an example of the appropriation and commercialization of lofts in New York City by an emergent social class of artists and creators who crystallized a pleasure-filled yet valid way of life that has extended beyond the term “alternative.”

This blend of people, programs, and exploratory lifestyles is lead by the increasing appeal of solitariness as a chosen lifestyle (Abalos, 141). The term solitariness, though, refers to the individual rejection of family and other repressive ties for the pursuit of a free and open way of life. This sociological mindset during the 1960’s through 80’s in urban areas in regards to the capitalist commune, is the culmination of the cult following of the intellectual works of Marx, Freud, and Wilhelm Reich. Where their works and ideas contrast, acts of liberation and rebellion among individuals intersect, to create the sociological mash of “solitary” communal living found in places like New York City during the 1970’s.

The deconstruction of these ideas, allows for Andy Warhol’s Factory as well as New York City to be read as an intensification of capitalism and collective living as an outlet for social, economic, and political freedom of expression. However, in order to apprehend the dynamic of the loft and the city under the influence of the collective and counterculture, one must understand how the alternative individual took on the role of the dweller and appropriator. What defines an individual and their so-called freedom? In his work, Karl Marx makes the claim that an individual is not in fact an individual, but a being defined by its surroundings, social groups, and class. Man only achieves relative freedom through social struggle. “Man does not invent anything, nor is he the person he imagines himself to be. He is the result of the nexus of material conditions of production and of social relations” (Abalos, 144). Meanwhile, the Freudian man is liberated through “an individual process of self-knowledge” (Abalo, 144), by recognizing the repressive conditions in which he has been raised and the unbalance and disequilibrium between himself and the rest of the world. Wilhelm Reich, a later figure, proposed to combine the two approaches to freedom and the collective.

Like his antecedents, Reich denounced the authoritarian family, and expelled them as the repressive force producing fearful individuals. His path to freedom, is through the collective and shared roles of society. He “proposes the commune as a new social axis of learning that connects the world-and world also means work- and self” (Abalo, 145). Though the ideologies of all three theorists differ, they all push towards the internal liberation of self, through rebellious social action. By rejecting the authoritarian family, and joining the collective, one can define and redefine their own self, and achieve their relative freedom through living and playing (and therefore learning) through a community. It is through this pedagogical mindset, that artists, creators, musicians, and socialites from all around the world, immigrated to New York City to experience the “wilderness” that was beginning to grow out of dwellings and into the city.

Because of the spatial memory of previously industrial production spaces like The Factory, lofts can be regarded as habitable typologies of the cave. Through the appropriation of the loft by the collective, the ideal home is broken down into particles resembling that of a livable space, but lacking the shades of privacy traditionally marked by architectural thresholds and boundaries. The loft becomes a spatial fusion of the urban collective, in which the space is not only used for living, but also for producing, networking, and celebrating. Conceptually and physically, thresholds are lacking, and rather than limiting the function of the loft, the collective transforms it into a profitable scheme for social and economic interaction, where artists and socialites could create, discuss, network, negotiate, and party. In the same way that the counterculture breaks down the thresholds of a home and creates a typology for the “much-frequented open house” (Abalo, 141), New York City grows into a village for the alternative individual and becomes the urban adaptation of a sociological and cultural shift towards the liberated and the collective idea for the dwelling.

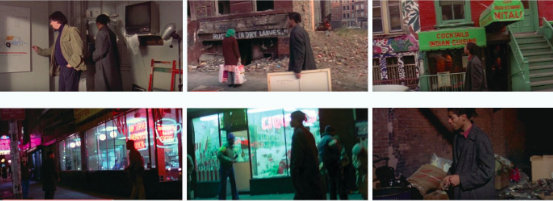

In the film Downtown 81, Jean Michel Basquiat is depicted experiencing and describing life as an artist in New York City during the early 1980’s. From the beginning of the film, Basquiat is shown constantly walking through the streets, into houses and hangouts, above ground, underground, and everything in between as if they were all one entity, as if there were little or no thresholds differentiating the city from the party. Basquiat himself becomes a personification of the city and its cultural shift towards the alternative counterculture, moving fluidly through various shades of programmatic space, sometimes leaving the viewer guessing if a space is private or public. Basquiat describes the wilderness of the city as the definition for his own work and his own self. In many instances, he plays himself as the city saying things like “the city looked big and I felt big. I was part of the landscape” or “I am a writer, but sometimes I feel like I was written [by the city].”

In the same way that Basquiat and Downtown 81 rigorously portray the artistic scene of New York City in the early 80’s one can visualize and imagine the environment created by the urban commune and the counterculture of the time. The appropriation of space by the urban collective creates a new kind of village, one that is about the alternative experience, and the relative liberation of the individual. Like the loft, parts of the city are appropriated to become networks for these people to communicate through and live in. By decentralizing New York City, clusters of urban collectives form micro communities within the larger spectrum of the city, and create a matrix of open houses for communards to freely pass through and experience. Neighborhoods like Soho became known as “slum incubators” and attest to the manifestation of the unorganized appropriation of space by the collective (Lee, 56).

Abstracted, a similar phenomenon can be found in the work of Gordon Matta Clark, whose life and projects define the essence of the counterculture and the physically and conceptually blurred threshold. Like Basquiat, Matta Clark lived the movement, and participated in the activities of the urban communes of New York City, even opening a restaurant, Food, in Soho for artists and creators to eat, network, and discuss art, architecture, and film. Spaces like these, address the collective appropriation of the city, and allowed the wilderness of the counterculture to expand into the streets and more public and open spaces of the city. In his work, his appropriation and transformation of existing architecture performs in parallel to the effects of the counterculture and the urban collective on the emergent micro communities in New York City during the 1960’s through 80’s. With an aggressive and anarchal approach, Matta Clark appropriates the city of New York in the 1960’s and 70’s to create large scale disruptions in existing urban conditions. His work literally punctures holes in the urban fabric to obscure the distinction between indoor, outdoor, the city, and the building. In this case, the cave is the city and the settler is Matta Clark.

The second typology for the cave, the shack, is a polar yet not entirely distorted version of the appropriated loft. Marc-Antoine Laugier, posited the shack as the first principle of architecture, the idea from which all theory extends; “If architecture is writing, the shack is speech” (Robertson, 154). In her essay Playing House, Lisa Robertson describes the shack as a single unit, a monad, saying that “Like any etymological construction, each shack is a three-dimensional modification of belief”(154). The projection of individual belief onto the shack is a reflection of the criteria for the dweller and their perception of economy and necessity.

As seen previously, the loft was a spatial recognition of the social shift towards an urban counterculture and alternative collective that freed itself from the thresholds of an ideal home to achieve the relative liberation of the individual inhabitant. Instead of portraying a growing trend or culture, the shack itself plays the image of a primitive foundation relative to architecture, but also to social and economic necessity. The degrees of social privatization that result from the appropriation of a primitive foundation, are guided by the same need to liberate the dweller from the organized and repressive separation of society and the natural landscape. Characterized by the desire to find relative freedom among the natural, the settler is attempting to withdraw from society and magnify their relationship to the organic. What the dweller craves is not solitude, but rather an image of origin heading into the future. The inhabited shack is a representation of the dweller’s anxious “retreat from lucid pleasure to protective opacity, then to willed structure” (Robertson, 151).

This liberation is seen in the economy of both the dweller and the shack itself. The minimal aspects and repurposed qualities of the construction of the shack as well as the material possessions of the dweller reflect the social withdrawal and relative economic and social freedom inherent in the shack. The characteristic of an inhabited wilderness embedded in the existence of the shack not only implies the intrinsic natural qualities of its location, but also redirects the dweller to the idea of a return to the uncontrolled social and economic origin of humanity. In Playing House, Robertson describes the economy of the shack saying that it enumerates necessity as a modern improvisatory ethos (152).

The unscripted qualities of the shack further intensify the idea of an inhabited wilderness, and the factors it must balance between the humane and the natural. Socially, economically, and possibly geographically, the shack must mediate the threshold between the timing of the incoming dweller and the landscape/spatial memory of the shack and its surroundings. The shack supplies a syntax for temporal passage, through which the dweller is able to reimagine the city from the image of the cave. Understanding the relationship between architecture and landscape that the shack must negotiate, both conceptually and architecturally, is crucial to apprehending it as an appropriation of space and time by a withdrawn inhabitant.

As Robertson says, “‘At last we know not what it is to live in open air… from the hearth to the field there is a great distance.’ It is the task of the shack to minimize this distance, in the service of an image of natural beauty” (153). Because of the shack’s withdrawn circumstance it becomes porous architecturally rather than socially to minimize the political, economic, and geographical divide between natural beauty, the shack dweller, and the rest of the population. The window replaces the wall, and opens the shack to its surroundings, creating a stronger and more unified relationship between the dweller and the landscape. The porosity of the shack to the landscape, liberates the dweller and returns them to nature and the organic in a way that fulfills the desire to privatize themselves.

In his book, Shifting Involvements: Private Interests and Public Action, Albert Hirschman explains that, “The term private was born as a negative concept, derived from the Latin privare-that is, to deprive someone of something, to dispossess someone of what he has. Thus private was a (negative) notion of subtraction, in relation to the positive one of public affairs, the commonwealth.” In the case of the shack, however, privacy is dynamic and engages and contains a multiplicity of layers and relationships with the exterior. When trying to understand the relationship of interiority and exteriority in the shack, it is to be noted that it is not one between public and private. Rather, the relationship being opened up by the lack of clear boundaries, is one about multiple degrees of privatization. Because the appropriated shack and nature are seen as a withdrawal from society and excess economy, the setting and landscape is already embedded with a certain degree of privacy. This is where the biggest distinction between the loft and the shack lies; despite the openness and porosity of the shack to the exterior, there is a juxtaposition in the shack’s inability to address the collective.

Prioritizing the individual before the community, the shack defends an idea of necessity and existence, rather than that of excess and pleasure. The settler of the cave, in the case of the shack, is likely coming from an urban or populated setting, where nature and landscape have been obscured among the artificial. The appropriation of the shack is the result of degrees of privatization in the search for a relative freedom. Through this separation and privatization, the community is excluded, and individual relationships between degrees of privacy replace the traditional connection between public and private.

While Thoreau’s original idea of the shack was to retreat into wilderness with minimal means and a necessity-based economy, modern society has attempted to privatize and commercialize this concept even more. The suburbs, as described by Robertson, are themselves appropriations of the model for the shack. Acknowledging the modern realities of urbanism, Robertson says “Suburbs are recurrent dreams. Each house repeats the singular wilderness. In the suburbs we learned to understand the virtual and now we invent the beginning, again, and again” (150). Through the deployment of suburban construction outside of urban areas across the country, consumers have access to the illusion of a temporal retreat from contemporary circumstances.

In both cases, whether urban or pastoral, there is a question of property ownership and commercialization that questions the porosity of the typologies to the collective or natural. If these spaces open up to external influences, is the owner (if there is one) compromising their property? To understand the complexities of property and shared domesticity, though there are various levels of privacy, it is helpful to revisit more specifically the work of Gordon Matta Clark, who addresses the ephemerality of occupied space within a larger context. In An Object to be Destroyed, Pam Lee addresses Hegel’s claims that property is structured around its use, and that its essence lies in “it being used and it vanishing.” In many ways, Matta Clark terminates the potential use of a building by permanently disrupting, vandalizing, or puncturing it, rendering the architecture useless. These perturbation in buildings and unusable spaces demonstrate the radical uselessness and the ambiguity by which things are demarcated as property (112).

Pam Lee describes property as “less of an extension of one’s person than the constitution of one’s being. The accumulation of these attributes, resulting in a bundle of properties, configures the identity of the subject in question” (111). In the case of New York City, the ordinary communard is constituted by the collective appropriation of Soho, not by a single loft or studio. The ordinary communard is constituted by the streets, the restaurants, and the lofts that are all openly shared and used as places for discussions, networking, and partying. The inhabitant of the shack, is constituted not just by their few possessions, but by the landscape and the construction of the shack itself. Thoreau, intentionally cataloging his belongings and furnishings, was conscious of how his possessions constituted his being. By understanding the necessity-based economy that the shack is based on, the shack’s dweller can negotiate and mediate the influence of the virtual.

While they are similar in their need to provide a “liberated” way of life for the dweller, the loft and the shed result in contrasting definitions of ownership, community, and the collective. The term “liberated” refers to the upbringing of each typology through the utopian dream of relative freedom by the dweller. While the loft rose out of an internal restlessness to expand socially, the shed resulted from a need to individualize and dislodge from society. The functional and social porosity of these alternative typologies of the cave blur the degrees of privacy internally and externally, creating a complexity in questions of property ownership and shared or individual domesticity in relationship to a larger community.

Bibliography/Works Cited

-Lee, Pamela M., and Gordon Matta-Clark. Object to Be Destroyed : The Work of Gordon Matta-Clark. MIT Press, 2000. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=24397&site=eds-live&scope=site.

-Iňaki Ábalos. “Warhol at the Factory: From Freudo-marxist Communes to the New York Loft”. The Good Life: A Guided Visit to the Houses of Modernity, 2017

- Lisa Robertson. “Playing House: A Brief Account of the Idea of the Shack”. Occasional Work and Seven Walks from the Office for Soft Architecture, 2011

-Georges Teyssot. “Windows and Screens” (excerpts: Scopic Regimes; Public and Private;

Framing the Gaze; Ethereal Spaces pp 252-274). A Topology of Everyday Constellations, 2013

-Niklas Maak. “Different Houses”; “After the House, Beyond the Nuclear Family”; “Transformations of Privacy”. Living Complex: From Zombie City to the New Communal, 2015