Architectural Theory

from “Conceptual Tectonics”

Professor Eunjeong Seong

December 2018

Yokohama in Motion

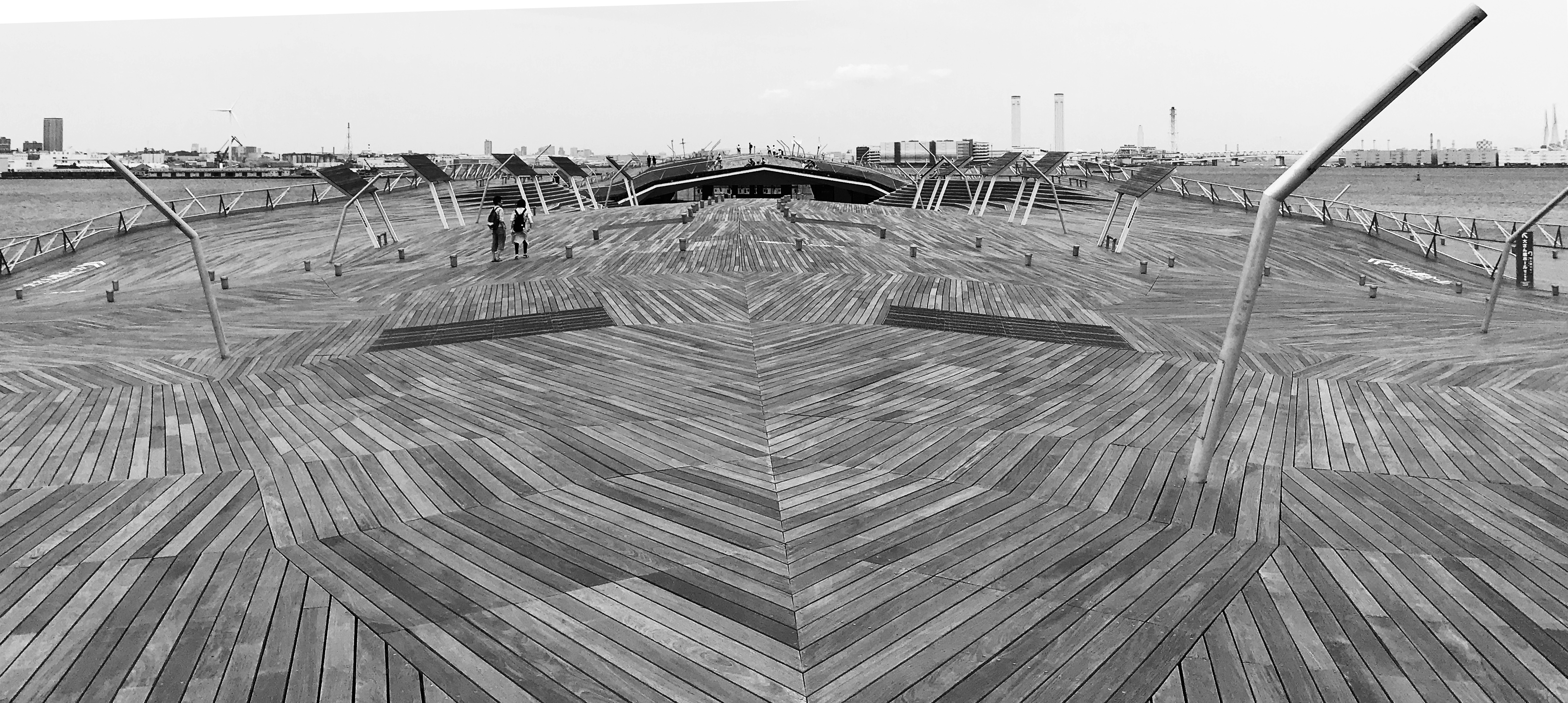

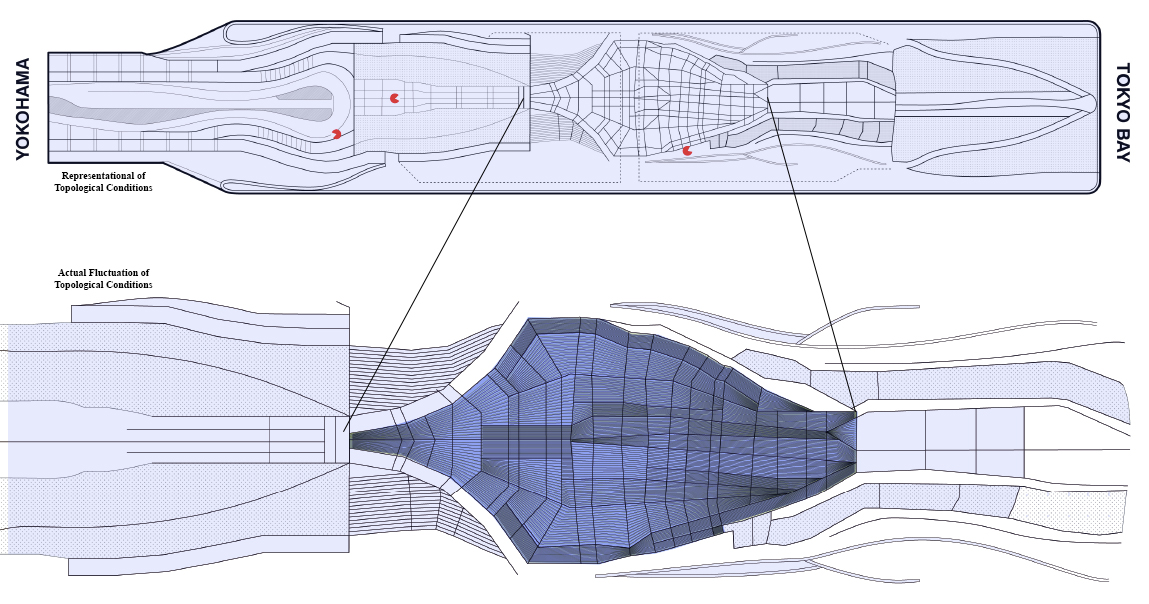

Built in 1995, the Yokohama International Passenger Terminal’s systematic and socially conscious thinking brought Foreign Office Architects (FOA) to the forefront of architectural design for the introduction of a fresh infrastructural typology. Made of three main levels that gradually move from private parking on the lowest level to fully public and exterior on the last level, the Yokohama Terminal, engages not only the basic necessities of a ferry terminal, but also the urban necessity to activate the public and generate a new kind of civic program.

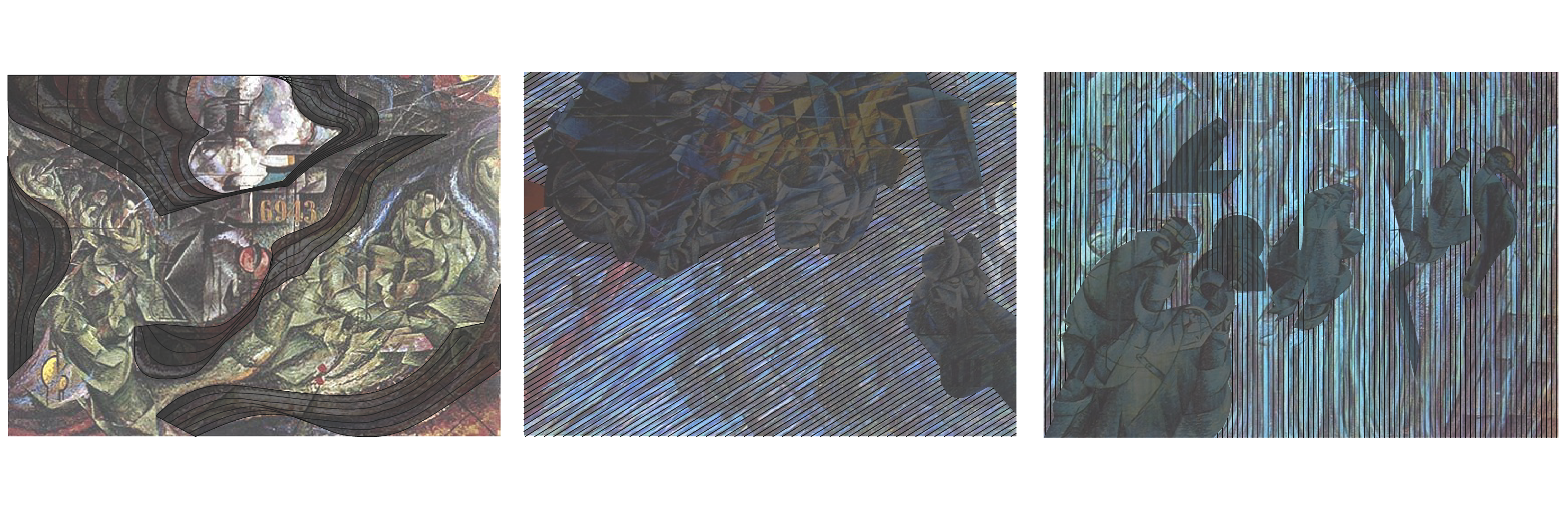

Through the compound collection of fragmented surfaces, Yokohama Terminal seems to exist within a realm of diverse planar realities, similar to the broken up subjects of Umberto Boccioni’s Stati D’Animo of 1912. Similarly to the analogous bright colors and bold striations in Stati D’Animo, Yokohama’s use of panelized wood implies the division of matter as well as a uniform being, and blend together the multidimensionality of the various segments. Piece by piece, the image comes together as a combination of lines and surfaces, that transform the canvas into a platform for multiple views and planar realms.

The part-to-whole relationship of the Yokohama Terminal, culminates into a dynamic and fluid network of both directional and deceptive striations that function as architectural ties from the city’s urban fabric to a smaller web of intimate interior and exterior circulation. It is crucial then, to analyze the Yokohama Terminal and its puzzle-piece components as singularities in a system of transformational moments for guiding a morphological and tectonic circulation and form.

When comparing Yokohama’s meshed complexity to artistic and architectural movements, one could begin to see the building and its visitors as dynamic futurist figures and representations in time and space. In his essay, Landscape of Change, Sanford Kwinter says, “The futurist universe - the first aesthetic system to break almost entirely with the classical one - could properly be understood only in the language of waves, fields, and fronts.” Similarly, Yokohama Terminal can begin to be read as a dynamized whole, broken into striated and linear fields with occuring singularities of transformational moments that are both tectonic and programmatic transitions.

Boccioni’s series, Stati D’Animo, depicts split and kaleidoscoped scenes at the moment that two passengers exchange goodbyes at a train station. Through the gradual futurist function of breaking and redeploying geometries as abstracted and dynamized formations, Stati D’Animo grows from a clear and almost cubic representation in the first painting, Gli Addii, to an almost fully striated canvas in Quelli Che Restano. The change in atmosphere from painting to painting happens as the entropy increases and the forms of bodies and objects further abstract into elementary matter.

This dynamical convergence of flows, as described by Sanford Kwinter, is “one scene, but three modalities of inhabiting matter (Landscape of Change, 53).” The matter Kwinter mentions is defined by Henri Bergson, as “modifications, perturbations, changes of tension or of energy and nothing else (Landscape of Change, 52).” Meaning that matter results from an activated system of singularities passing through constant transformational events. When dissected and analyzed as formulations of matter and time, rather than as whole images on flat surfaces, the three paintings begin to behave independently of each other and of the shared depiction.

A closer look at the panelization of Yokohama Terminal’s exterior platform, raises the idea of movement and motion through the dynamicity achieved in the aggregation of simple planar surfaces. The main level, which appears to function as one undulating surface for public use, is actually made up of a very active set of smaller planes, which are further broken up by the linearity of the wood panels. At this scale, the singularities created by the rigorous fragmentation of exterior surface, can be defined as results of a systematic sequence of transformational tectonic events. This kind of superficial transformation can be similarly compared to the abstraction and redeployment of matter in the cubist and futurist approach to the depiction of the dramatic scene in Quelli Che Restano. Here, forms and figures are clearly visible through the blue blades that cut across and transform the scene.

Though the broken linearity of the exterior envelope of Yokohama Terminal appears to be part of a superficial formal or tectonic series of transformations, the organization and program of the building seem to be part of a much larger scale of transformational events. Still looking at the main exterior platform, one can observe a series of transformational programmatic and circulatory events that create a morphological change from flat wood panels into an almost widened field of peeling stairs and surfaces. In the same way that Stati D’Animo’s entropic representational characteristics and atmospheres, such as diagonal breaks from linear and radial divisions, and straight cuts of bright color, are precise results of the futurist manifesto on the simple context of each painting, the morphology and discontinuity of the panels and steps in Yokohama Terminal are direct responses to FOA’s programmatic agenda.

Looking at the middle entrance of Yokohama Terminal from the exterior, it can be seen that without the programmatic decision for the entrance to be placed exactly there and with those dimensions, the planar surfaces on the landscape of the platform would not morph to create lifted stepping and peeling conditions that dip down into a cavelike entry. Kwinter defines this kind of localized and specifically programmatic transformation as a catastrophe. “A catastrophe describes the way in which a system - sometimes as a result of even the most infinitesimal perturbation - will mutate or jump to an entirely different level of activity or organization (Landscape of Change, 58). ”

The further, larger, fragmentation of the building through programmatic organization, can be compared to the second painting of the Boccioni series, Quellli Che Partono, not because of the painting technique or the futurist ideals, but because of its role in the three part series. The change happens at a larger scale than that of an individual painting; it happens at the convergence of the three paintings. “Quelli Che Partono no longer describes a convergence of flows but rather the event of their breaking up, or bifurcation. [...] The painting Quelli Che Partono wedges its own diagonal cascades and chevron forms between its two neighbor panels: on one side, the undulating, orbicular, systolic-diastolic processes of organicism and embrace depicted in Gli Addii, and, on the other, the inertial, gravity-subjugated, vertical striations of Quelli Che Restano. [...] Between the first panel and the other two, there had taken place a catastrophe (Landscapes of Change, 53).”

From the urban landscape, the pedestrian is greeted with a clear direction pointing to an almost clearer vantage point. Once the user advances further into the building, the panelization and directionality of the wood start to slightly deviate and point the pedestrian in different directions, which lead to various programmatic interior and exterior conditions. Considering these conditions as localized catastrophes, would create a map of transformational moments linking the interior with exterior. These catastrophic moments, though sensibly organized in plan, are not about the localization in relation to each other or the building, but instead they are about the trajectories visitors had to take in order to reach those positions. Kwinter says, “The point here is that the conditions on the dynamical plane are very erratic, and mere position means far less than the pathway by which one arrives there. Catastrophe theory specializes in accounting for these situations (Landscape of Change, 60).” This is the moment at which point the scales of the singularities and transformational events at Yokohama Terminal, mesh with the programmatic scene of the building, to create a full web of scalar circulation and localized program, where the user more than anything is prioritized.

Formally and conceptually, Yokohama Terminal functions with an intense and dynamic fluidity, similar to the themes of the futurist movement. Not unlike the beliefs of Filippo Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni, and other futurist leaders, FOA boldly chooses to celebrate modernity and the triumph of technology. This stance is seen not only through the magnitude of the scale of the terminal, but through the rigorous tectonic and formal strategies applied in the multiplicity of surface. A futurist approach to the building is not only seen through a technological lense pointing at the complex construction, but also seen in the intent to dynamize and activate the building through its program and inhabitation. Without the user, the building stands still, and static, with clear thresholds and defined limits. Catastrophic moments still occur, but in a motionless and desensitized way without an impact on function.

Bibliography/ Works Cited

-Sanford Kwinter, Landscapes of Change: Boccioni’s Stati d’animo as a General Theory of Models (1992) The MIT Press.

-Greg Lynn, Animated Form, 1999, Princeton Architectural Press

-Excerpt from: Umberto Boccioni E La Pittura Degli Stati D’animo

-http://losbuffo.com/2017/12/23/umberti-boccioni-stati-danimo/